Morocco is living a moment of emotional density that is difficult to summarize in a single feeling.

These days, grief and joy are not successive states; they coexist. They overlap. They contradict one another without cancelling each other out.

There is pain. A collective, social, sometimes silent or silenced pain linked to recent losses, hardships, and unresolved wounds.

And there is also excitement, pride, and anticipation as the country turns its eyes toward the Africa Cup of Nations, an event that mobilizes hearts, streets, and conversations.

At first glance, this emotional coexistence may appear incoherent. How can a society mourn and celebrate at the same time? How can sadness and enthusiasm share the same psychological space? Yet, from a clinical perspective, this simultaneity is neither pathological nor exceptional. It is profoundly human. It reflects a capacity to remain alive to experience, instead of freezing within a single affect.

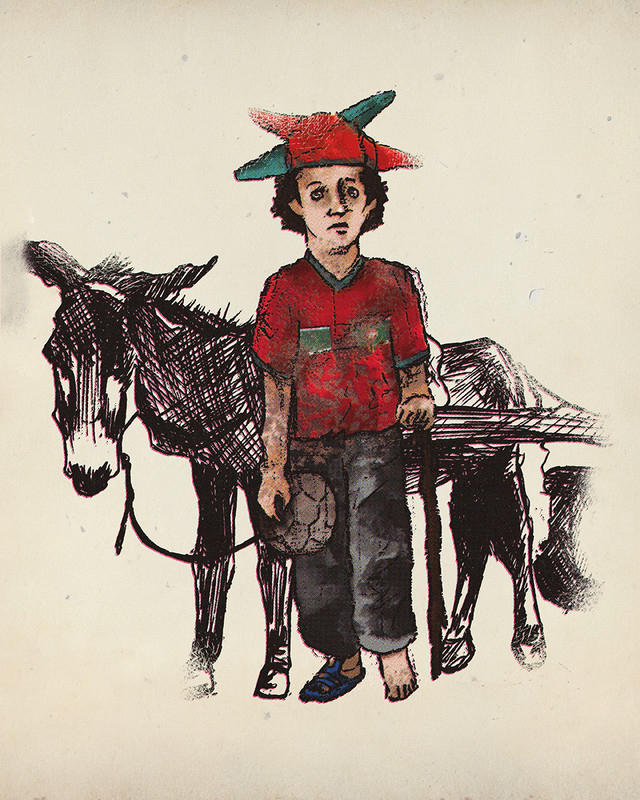

In Morocco, collective emotions are rarely experienced in isolation. They are shaped by family ties, neighborhood life, shared histories, and a strong sense of belonging. Grief is not only private; it is socialized. Joy, too, is rarely solitary. Football becomes a symbolic container for hope, identification, and emotional release. It offers a momentary suspension of heaviness, a shared rhythm, a language understood across generations and social classes. And beyond sport, the Africa Cup of Nations also carries a deeper symbolic dimension. It is a decolonial football event, bringing together peoples whose histories are marked by colonization, apartheid, political violence, and structural inequalities. It is also a space of collective affirmation, dignity, and visibility. For many African societies, football becomes one of the rare arenas where pride, unity, and historical continuity can be publicly expressed without mediation, and it is tied to long-standing narratives of resistance, survival, and collective identity.

But joy does not mean denial, or forgetting a loss. Holding multiple emotions simultaneously is a psychological task that requires symbolic space. Without spaces for speech, listening, and recognition, emotions tend to overflow through violence, withdrawal, somatic symptoms, or burnout. Public joy can coexist with private pain, but only if pain is allowed to exist somewhere: to be named, heard, and legitimized. When society implicitly demands one emotion at the expense of another, when people are told it is “not the time” to grieve because there is a match, this moralization of emotions creates guilt and silencing. It overlooks the fact that individuals and communities do not function on a single emotional register.

At a political level, this tension is not neutral. The Moroccan regime, like many others, invests heavily in symbolic events that serve a narrative of unity, success, and international recognition. Moments of collective celebration can become tools of propaganda, not to transform the lived reality of the people, but to impose an image that must be believed, defended, and displayed. Events that disrupt this narrative like grief, protest, anger, mourning, are then experienced as threats, as disturbances that “ruin the picture.” In such contexts, the problem is not joy itself, but the demand that joy becomes exclusive, compulsory, and performative. When image takes precedence over lived experience, when appearances matter more than addressing social suffering, individuals are subtly pushed to silence their pain in order not to disturb the collective illusion.

This dynamic does not resolve suffering; it displaces it, often at a psychological cost. This is where splitting emerges. Splitting transforms emotional differences into rigid camps, where people are either seen as insensitive celebrators or moralized mourners, rather than as individuals navigating mixed and legitimate affects. Splitting refers to a primitive way of managing anxiety by dividing the world, and others, into opposing categories: good versus bad, legitimate versus illegitimate, those who “feel the right way” versus those who supposedly do not. More concretely, splitting consists in placing all our positive feelings in one place and all our negative feelings in another, because holding them at the same time feels too difficult. This psychological shortcut temporarily reduces inner tension, but at the cost of complexity.

Psychoanalysis also describes another position beyond splitting: the depressive position. Unlike splitting, it emerges when an individual can tolerate ambivalence, the unsettling realization that nothing and no one is entirely good or entirely bad. It is called depressive not because it reflects pathology, but because it is emotionally demanding. It requires giving up idealized images, accepting loss, and holding contradictory feelings at the same time. In other words, it is “depressing” because it confronts us with complexity. Reaching the depressive position requires psychological maturity and compassion, toward oneself and toward others. From this position, grief does not cancel joy, and joy should not deny suffering. No emotion negates or erases any other. What changes is not the presence of pain or excitement, but the capacity to contain them without turning them into moral judgments or social divisions.

In times like these, the challenge is not to choose between mourning and celebration, but to make room for both, without propaganda, without guilt, and without denying the emotional truth of lived experience.